By: Anika Perry

Edited by: Kimberly Johnson and Roderick Perry

My first year of teaching had come to an end and just as most teachers, I eagerly went online to check my Georgia Milestones (GMAS) results. The GMAS are accountability exams for all public school students in grades 3-12 in Georgia. I quickly typed away, barely containing myself, excited to see how well my students performed. Then, there in big bold numbers and letters were the dreaded results—My class had a 51% pass rate on the ELA (English Language Arts) GMAS. I slumped! How did this happen? I immediately went into repair mode. How could I use my reflective practices to change future outcomes?

The Faulty First Year

According to Kameenui, Dixon, and Carine (1987), “Rote memorization of words and definitions is the least effective instructional method resulting in little long-term effect.”

I remember the day that I had worked so hard for in college had finally come to fruition. I was hired as a 4th grade ELA teacher! Still in disbelief that my dream had come true, I hit the ground running to prepare for the upcoming school year. In preparation, I gathered my spelling lists, vocabulary lists, grammar practices, and a plethora of comprehension passages. I was PUMPED! I felt that I was ready to take on the year. By the first day, I had double checked to make sure that I had prepared my copies, reviewed the standards, and had all my worksheets in order! Now it was time for instruction and assessment. My schedule was easy and would amount to great gains, or so I thought. I initially decided to give spelling, vocabulary, and grammar tests every week. I received failure after failure after failure. I reflected and thought that perhaps the students just needed additional days to study so instead of giving the lists and grammar for the week on Mondays, I gave it the previous Fridays instead. After all, students would love to spend the weekend studying in advance. The outcome was still failure after failure. I expressed my concerns to my colleagues regarding the inefficient scores on spelling, vocabulary, and grammar tests, but I was encouraged to continue my practices or shorten the list. I pressed on even though I knew the practice continued to be counterintuitive to student achievement.

“If we really want our students to become wild readers, independent of our support and oversight, sometimes the best thing we can do is get out of the way.” Donalyn Miller

New week, new story. Following the direction of others, I prepared the story of the week based on the SRA Imagine It! book. I read the story in advance to make sure that I comprehended and could answer any student questions regarding the text. Additionally, I made sure to emphasize and review the vocabulary words as we read. Easy enough, I thought, because students learn from repetition, right? I decided that my instructional practices for the week would vary from listening to the audio of the story, me reading the story to the class, students reading the story with a partner, and independent reading of the story on Friday. Like it or not, they were going to have some sort of engagement with the text every day. Then came the Friday comprehension test. We had read or listened to the story every day of the week so I knew for sure that students were going to pass. As with the spelling and vocabulary lists these, too, resulted in a high failure rate. What. Was. I. Doing. Wrong?!

I reflected and realized that my classroom practices were composed of direct instruction, a lack of independent and guided reading, and a lack of differentiation to meet student needs. I knew my practices had to change, but being a new teacher, I did not know where to begin. At the end of my second year, I decided it was time to move closer to home, and hopefully, I would work in a school in which I could improve my instructional practices. Luckily, I did.

New School, New Practices

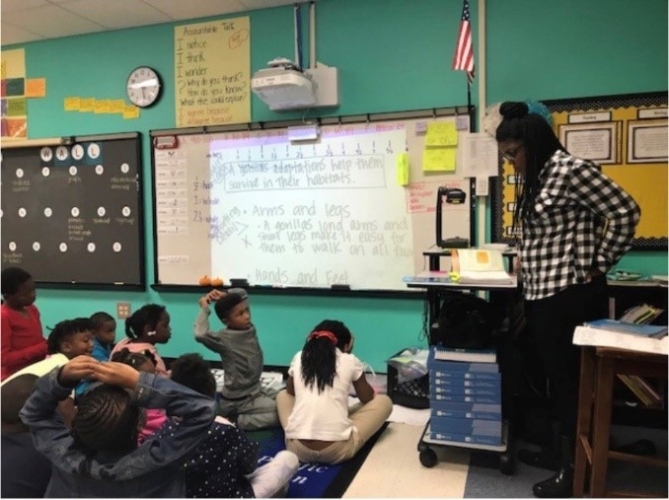

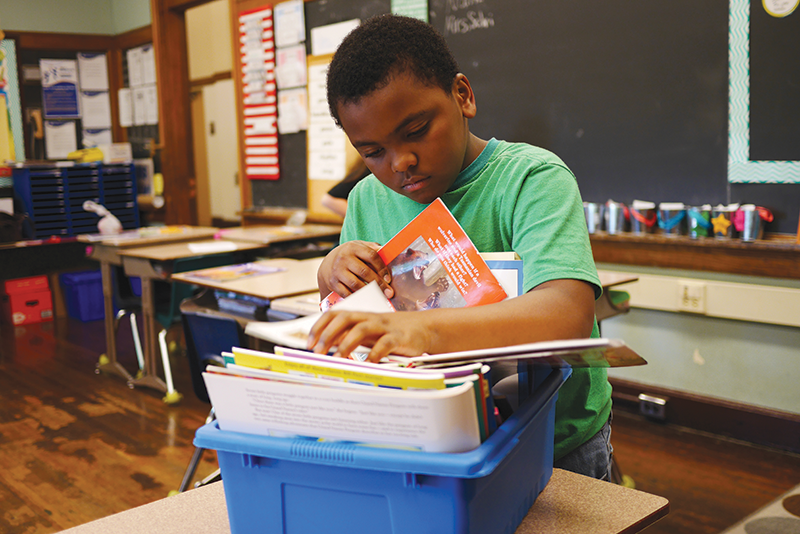

I approached my fresh start with the adage, “Out with the old and in with the new” in the forefront. Out were the spelling and vocabulary tests and unintentional instruction. EVERYTHING from this point on became intentional. With the support of a phenomenal administrative staff and reading coach, I implemented guided reading to support developing learners excel as readers. I leveled my classroom library which provided students with immediate access to over 250 books in a variety of genres so they could apply instructional strategies that were learned during the minilesson.

Additionally, I drastically reduced my direct instruction to about 12 minutes per lesson. Understanding by Design became my driving force behind intentional instruction. With Understanding by Design, I could foresee potential setbacks with the unit and plan for them in advance. I implemented the use of pre-assessments so I could teach into student deficits and be more intentional with my instruction. I also gave post assessments so that I could get an accurate depiction of student growth and plan next steps for students that lacked mastery.

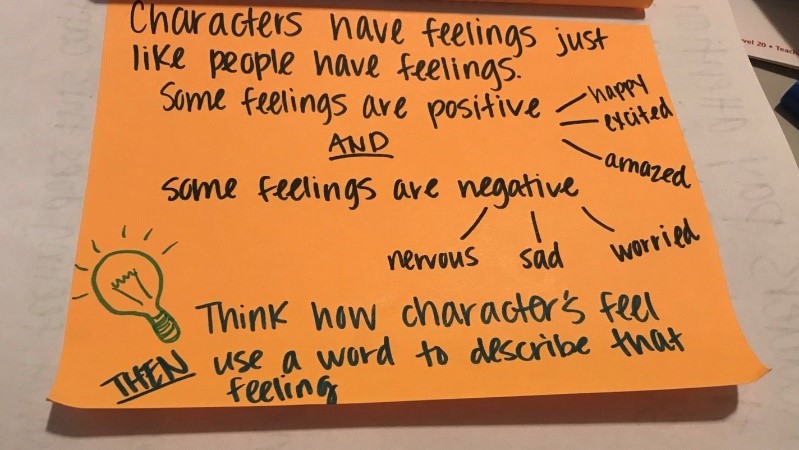

Additionally, the use of mentor texts was implemented as a teaching tool to help with the transfer of skills. I worked hard, but my students worked even harder. They thrived with this “new” student-centered way of teaching and by the end of the year, results confirmed the power of intentional instruction. I had an 81% pass rate all while teaching all subjects. The work was not done, I realized I had made significant gains, but I knew I could grow even more so I developed a plan to help me achieve even more for the upcoming 2018-2019 school year.

And Then What?

As I prepare to begin my fourth year of teaching, I want to mimic the successful year I had last year—I must! Constant reflection and openness to change as I go helps me improve as a teacher. As I move on to teach fifth grade, I intend on incorporating more one-on-one conferences, taking a closer lens to the mentor text, and incorporating more inquiry based learning. If I’m intentional, my students will be intentional. As Grace Chough, Staff Developer at the Teachers College of Reading and Writing Project, stated, “It’s all about helping kids be intentional.” And that, fellow educators, parents, volunteers, and general public is how I transformed my teaching, because I became intentional!

About the Authors:

Anika Renece Perry (Writer) is a 5th grade English Language Arts teacher in Fulton County, Georgia. She enjoys teaching and inspiring the youth. She attended Valdosta State University and obtained her Bachelor of Science in Early Childhood/Special Education and her Master of Science in Early Childhood. She is a United States Armed Forces Veteran and honorably completed six years in the Air Force and deployed to both Qatar and Afghanistan. In her free time, she enjoys volunteering, reading, and working on home improvement projects.

Anika Renece Perry (Writer) is a 5th grade English Language Arts teacher in Fulton County, Georgia. She enjoys teaching and inspiring the youth. She attended Valdosta State University and obtained her Bachelor of Science in Early Childhood/Special Education and her Master of Science in Early Childhood. She is a United States Armed Forces Veteran and honorably completed six years in the Air Force and deployed to both Qatar and Afghanistan. In her free time, she enjoys volunteering, reading, and working on home improvement projects.

Kimberly Johnson (Editor) teaches eighth and ninth-grade creative writing and reading for at-risk students at Auburn (Alabama) Junior High School. Nationally board-certified in early adolescent language arts in 2004, Kimberly started teaching language arts in 1998 at Cedar Ridge Middle School in Decatur before moving to Auburn in 2004. Originally from Anniston, she received a degree in communications from the University of Alabama, a master’s in language arts education from Alabama A&M University, and an education specialist’s degree in English language arts education from Auburn University. She and her husband, Jeff, have three children, Jouri, Jaden, and Jayme, and she serves as a mentor and teacher-leader at Auburn Junior High and with Auburn City Schools.

Kimberly Johnson (Editor) teaches eighth and ninth-grade creative writing and reading for at-risk students at Auburn (Alabama) Junior High School. Nationally board-certified in early adolescent language arts in 2004, Kimberly started teaching language arts in 1998 at Cedar Ridge Middle School in Decatur before moving to Auburn in 2004. Originally from Anniston, she received a degree in communications from the University of Alabama, a master’s in language arts education from Alabama A&M University, and an education specialist’s degree in English language arts education from Auburn University. She and her husband, Jeff, have three children, Jouri, Jaden, and Jayme, and she serves as a mentor and teacher-leader at Auburn Junior High and with Auburn City Schools.

Roderick Perry (Editor) is the current Director of Athletics at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. He has extensive collegiate experience in strategic planning, budget management, compliance, public relations and donor cultivation. Before IUPUI, he served in administrative posts at Wright State, Florida and Auburn. He earned undergraduate and master’s degrees from Auburn and a doctorate in educational leadership from Dayton.

Roderick Perry (Editor) is the current Director of Athletics at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. He has extensive collegiate experience in strategic planning, budget management, compliance, public relations and donor cultivation. Before IUPUI, he served in administrative posts at Wright State, Florida and Auburn. He earned undergraduate and master’s degrees from Auburn and a doctorate in educational leadership from Dayton.

Leave A Comment